ALL ABOUT GREYHOUNDS: The History of the Greyhound

by Dr. Jim Jeffers, GreySave volunteer

For thousands of years Greyhounds have been bred to hunt by outrunning their prey. They were not intended to be solitary hunters, but to work with other dogs. Switching from hunting to racing has kept this aspect of their personality very much alive. The fastest breed of dog, Greyhounds can reach a top speed of 45 miles per hour, and can average more than 30 miles per hour for distances up to one mile. Selective breeding has given the Greyhound an athlete's body with the grace of a dancer. At the same time, the need to anticipate the evasive maneuvers of their prey has endowed the Greyhound with a high degree of intelligence. (Above: Roman mosaic of running Greyhound-type dog, House of Dionysus, Paphos, Crete, second century AD.) Metropolitan Museum of Art - Slideshow on Greyhounds in Art Gary Tinterow, Engelhard Chairman of the Department of Nineteenth-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City,has been adopting former racing greyhounds from adoption groups for over 20 years. He has posted a four-minute narrated slideshow on greyhounds in art. He says that the greyhound is the only dog whose representation in art has remained essentially unchanged for 5,000 years. He also talks about what it's like to live with greyhounds. See his slideshow on Greyhounds in art. The modern Greyhound is strikingly similar in appearance to an ancient breed of sighthounds that goes back to the Egyptians and Celts. Dogs very similar to Greyhounds--domesticated hunters with long, slender bodies-- appear in temple drawings from 6,000 BC in the city of Catal-Huyuk in present-day Turkey. A 4,000 BC funerary vase found in the area of modern Iran was decorated with images of dogs looking much like Greyhounds. Since ancient artists tended to depict only images of religious or social significance to their societies, these dogs must have been fairly important to the peoples of those days. We do not know for certain that these dogs are forerunners of the modern Greyhound. How Racing Works

Nearly all US racetracks are quarter-mile ovals. Eight to twelve dogs compete per heat, with 13 heats a day the norm. Races range from 5/16ths to 9/16ths of a mile and last about 30 seconds. Earth Call holds the world record for the 5/16ths-mile course with a time of 29.59 seconds, while P's Rambling has the 3/8ths-mile record at 36.43 seconds. The Caliente Racetrack in Tijuana, Mexico, from which many of our Greyhounds come, runs 13 races every night and matinee performances on weekends. The races are 5/16ths and 7/16ths of a mile. The dogs are weighed two hours prior to running and are examined by a veterinarian and a paddock judge. They are next blanketed and muzzled, and taken onto the track for the pre-race parade. At race time the Greyhounds are put in the starting box, the artificial lure comes around the track, and the box opens. Drug testing is conducted after each race. Each state has its own rules regarding the grading system. The most common grades are A, B, C, D, E, J, and M. Most states also have S for stake races and T for races with mixed grades. Some tracks, such as Wonderland, Gulf, and Lincoln, have a top grade of AA. Some tracks also have a Grade BB. Caliente also races grades D and E. |

American Coursing

Competitive coursing is an amateur sport in the United States today. The Greyhounds compete for honors, not money. No gambling takes place. Due to concerns over humane treatment of hares, live hares have been replaced by artificial drag lures.

The course is typically 800 yards long. A white plastic bag is attached to a thin line strung along a series of pulleys in the ground. A motor winds up the line, causing the bag to mimic the movements of a hare. As the image to the left indicates, the Greyhound's front legs are usually wrapped to prevent cuts from the line.

The Racing Secretary is responsible for the proper grading of the Greyhounds under the provisions outlined by the state. Before the opening of the race meet, the Racing Secretary, after schooling all Greyhounds, and considering their past performance, assigns the Greyhounds to a proper grade. As a Greyhound wins a race it advances one grade until reaching A. The winner of a M (maiden) race advances to Grade D or in some states Grade J (new, non-maiden dogs).

The Racing Secretary may reclassify a Greyhound at any time, but not more than one grade higher or lower. Generally if a Greyhound fails to finish first, second or third, in three consecutive starts (except in Grade E or M), or fails to earn more than one third in four consecutive starts in the same grade, that Greyhound will be lowered one grade.

Greyhounds in lower grades are given more opportunities to race in the money before being ruled off. A Greyhound doesn't have to win in order to stay active. For example, a Greyhound named Jamie's Simoneyes ran 170 races with no wins.

Most racetracks in America have a kennel compound, including 16-20 independently-operated kennels, housing the approximately 1,000 Greyhounds needed to operate the track. Greyhounds must be leased to one of those kennels by their owners in order to run at that track. Normally the kennel owner takes 65 percent and the dog owner 35 percent of the Greyhound's earnings.

In the past, Greyhounds typically were moved from track to track as various racing seasons ended. Year-round racing now keeps many dogs in one geographical area. A consistent racer may spend its entire career at only one or two tracks. However, dogs whose performance improves or declines still may be moved to higher- or lower-graded tracks.

The Greyhound Hall of Fame in Abilene, Kansas, sponsored by the US racing industry's National Greyhound Association, features famous American racing Greyhounds. The most important race in the US is the Greyhound Race of Champions, sponsored by the American Greyhound Track Operators Association. Held since 1982, it attracts the top Greyhounds in the nation.

Other top stakes are the Wonderland Derby near Boston, the Sunflower Stake at the Woodlands in Kansas City, and the American Derby at Lincoln, Rhode Island. Since 1970, the Irish-American Classic has matched the best Irish Greyhounds against the best of the US.

Competitive coursing is an amateur sport in the United States today. The Greyhounds compete for honors, not money. No gambling takes place. Due to concerns over humane treatment of hares, live hares have been replaced by artificial drag lures.

The course is typically 800 yards long. A white plastic bag is attached to a thin line strung along a series of pulleys in the ground. A motor winds up the line, causing the bag to mimic the movements of a hare. As the image to the left indicates, the Greyhound's front legs are usually wrapped to prevent cuts from the line.

The Racing Secretary is responsible for the proper grading of the Greyhounds under the provisions outlined by the state. Before the opening of the race meet, the Racing Secretary, after schooling all Greyhounds, and considering their past performance, assigns the Greyhounds to a proper grade. As a Greyhound wins a race it advances one grade until reaching A. The winner of a M (maiden) race advances to Grade D or in some states Grade J (new, non-maiden dogs).

The Racing Secretary may reclassify a Greyhound at any time, but not more than one grade higher or lower. Generally if a Greyhound fails to finish first, second or third, in three consecutive starts (except in Grade E or M), or fails to earn more than one third in four consecutive starts in the same grade, that Greyhound will be lowered one grade.

Greyhounds in lower grades are given more opportunities to race in the money before being ruled off. A Greyhound doesn't have to win in order to stay active. For example, a Greyhound named Jamie's Simoneyes ran 170 races with no wins.

Most racetracks in America have a kennel compound, including 16-20 independently-operated kennels, housing the approximately 1,000 Greyhounds needed to operate the track. Greyhounds must be leased to one of those kennels by their owners in order to run at that track. Normally the kennel owner takes 65 percent and the dog owner 35 percent of the Greyhound's earnings.

In the past, Greyhounds typically were moved from track to track as various racing seasons ended. Year-round racing now keeps many dogs in one geographical area. A consistent racer may spend its entire career at only one or two tracks. However, dogs whose performance improves or declines still may be moved to higher- or lower-graded tracks.

The Greyhound Hall of Fame in Abilene, Kansas, sponsored by the US racing industry's National Greyhound Association, features famous American racing Greyhounds. The most important race in the US is the Greyhound Race of Champions, sponsored by the American Greyhound Track Operators Association. Held since 1982, it attracts the top Greyhounds in the nation.

Other top stakes are the Wonderland Derby near Boston, the Sunflower Stake at the Woodlands in Kansas City, and the American Derby at Lincoln, Rhode Island. Since 1970, the Irish-American Classic has matched the best Irish Greyhounds against the best of the US.

1990s: Racing's High Point

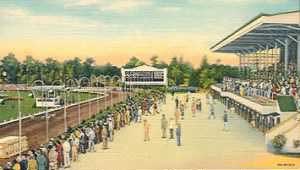

By the 1990s Greyhound racing had become one of the most popular spectator sports in America. Attendance at tracks was nearly 3.5 million in 1992. The over 50 tracks in America ran a total of 16,827 performances in 1992, over which fans wagered almost $3.5 billion. The largest track was Gulf Greyhound Park near Houston, with an average attendance of 5,000 for each of its 467 performances in 1992. (Above: Greyhound racing postcard from the 1930s.)

Racing's Slow Decline

Greyhound racing hit hard times in the late twentieth century, in both Great Britain and the United States. In Britain, its popularity declined in the 60s. Many tracks closed in the 1970s and 1980s, and the industry experienced ups and downs in the 1990s.

In the U.S., Greyhound racing has steadily lost popularity since 1992. Between 1991 and the end of 2009 25 tracks closed, leaving 34 in operation by the American Greyhound Track Operators Association (AGTOA) in 13 states and Tijuana, Mexico (the location of the the Caliente Racetrack, from which GreySave gets most of its hounds). Revenues have dropped by more than 50 percent since 1992.

The decline is due in part to state bans on racing. States that have banned racing since the 1990s are: Idaho, Maine, North Carolina, Nevada, New Hampshire, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Pennsylvania. But the decline is mostly due to the rising popularity of other forms of gambling such as Indian casinos, riverboat gambling, and lotteries.

See a Map of Greyhound Tracks which indicates which tracks have closed in recent years and which ones are still operating. As of March 2010, 24 U.S.-sanctioned greyhound tracks were still operating in the U.S. and Tijuana, Mexico.

The Life of the Racing Greyhound

For the first year of their lives Greyhound puppies live together with their litter mates and are handled frequently by the breeders and other staff associated with the breeding "farm," but they are not exposed to other breeds of dogs. As a result, they often do better with unknown people than with other breeds of dog. They are given a lot of exercise in large pens that allow them to run at full speed. Training starts at about 8 wks of age, as they race each other in runs that are 250-300 ft long.

They are placed in individual crates in the kennel between 4-18 months of age, where they spend most of their time between exercise periods and training. The crate becomes the dog's refuge from other dogs. At 6 months of age their training starts in earnest.

Training with the drag lure begins around 10 to 12 months of age. A mechanical device drags an artificial lure along the ground so the puppy can see it and pursue it. By age 18 months, their training usually is over and they are sent to the track. They are given six chances to finish in the top four in their maiden race. If they do not, they are retired--put up for adoption or euthanized. The best runners go to the most competitive tracks.

By the 1990s Greyhound racing had become one of the most popular spectator sports in America. Attendance at tracks was nearly 3.5 million in 1992. The over 50 tracks in America ran a total of 16,827 performances in 1992, over which fans wagered almost $3.5 billion. The largest track was Gulf Greyhound Park near Houston, with an average attendance of 5,000 for each of its 467 performances in 1992. (Above: Greyhound racing postcard from the 1930s.)

Racing's Slow Decline

Greyhound racing hit hard times in the late twentieth century, in both Great Britain and the United States. In Britain, its popularity declined in the 60s. Many tracks closed in the 1970s and 1980s, and the industry experienced ups and downs in the 1990s.

In the U.S., Greyhound racing has steadily lost popularity since 1992. Between 1991 and the end of 2009 25 tracks closed, leaving 34 in operation by the American Greyhound Track Operators Association (AGTOA) in 13 states and Tijuana, Mexico (the location of the the Caliente Racetrack, from which GreySave gets most of its hounds). Revenues have dropped by more than 50 percent since 1992.

The decline is due in part to state bans on racing. States that have banned racing since the 1990s are: Idaho, Maine, North Carolina, Nevada, New Hampshire, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Pennsylvania. But the decline is mostly due to the rising popularity of other forms of gambling such as Indian casinos, riverboat gambling, and lotteries.

See a Map of Greyhound Tracks which indicates which tracks have closed in recent years and which ones are still operating. As of March 2010, 24 U.S.-sanctioned greyhound tracks were still operating in the U.S. and Tijuana, Mexico.

The Life of the Racing Greyhound

For the first year of their lives Greyhound puppies live together with their litter mates and are handled frequently by the breeders and other staff associated with the breeding "farm," but they are not exposed to other breeds of dogs. As a result, they often do better with unknown people than with other breeds of dog. They are given a lot of exercise in large pens that allow them to run at full speed. Training starts at about 8 wks of age, as they race each other in runs that are 250-300 ft long.

They are placed in individual crates in the kennel between 4-18 months of age, where they spend most of their time between exercise periods and training. The crate becomes the dog's refuge from other dogs. At 6 months of age their training starts in earnest.

Training with the drag lure begins around 10 to 12 months of age. A mechanical device drags an artificial lure along the ground so the puppy can see it and pursue it. By age 18 months, their training usually is over and they are sent to the track. They are given six chances to finish in the top four in their maiden race. If they do not, they are retired--put up for adoption or euthanized. The best runners go to the most competitive tracks.

Twentieth Century

California Hosts the First Modern Greyhound Racetrack

Around 1910, Owen Patrick Smith invented the mechanical lure. In 1919 Smith opened first oval Greyhound racetrack in the U.S. in California (in Emeryville). Six years later he owned 25 tracks around the nation, including ones in Florida, Montana, and Oregon. Florida became the US capital of the sport after dog racing was introduced there in 1922. The first track race in England opened in 1926. Greyhound racing became very popular with the working classes in America and Britain. Before long it spread to Ireland and Australia as well. (Above: Greyhound racing in the early 20th century.)

California Hosts the First Modern Greyhound Racetrack

Around 1910, Owen Patrick Smith invented the mechanical lure. In 1919 Smith opened first oval Greyhound racetrack in the U.S. in California (in Emeryville). Six years later he owned 25 tracks around the nation, including ones in Florida, Montana, and Oregon. Florida became the US capital of the sport after dog racing was introduced there in 1922. The first track race in England opened in 1926. Greyhound racing became very popular with the working classes in America and Britain. Before long it spread to Ireland and Australia as well. (Above: Greyhound racing in the early 20th century.)

The Birth of Competitive Racing

With the formation of the National Coursing Club of England in 1858, coursing was turned into more of a business. It began requiring the registration of dogs for its events in 1882. This led to the creation of The Greyhound Stud Book in Britain and, later, sister publications in the US, Ireland and Australia.

The evolution from coursing to track racing began in 1876, when the first enclosed or "park" course meet was held. These courses were only 800 yards long instead of the 3-mile traditional courses. Because of this, enclosed courses put a premium on speed. Enclosed courses have stayed very popular in Ireland.

Their popularity in England was short-lived, but they helped convince open coursing leaders to shrink the size of their courses. Also in 1876, Greyhound racing began at the Welsh Harp, Hendon, England, when six dogs raced down a straight track after a mechanical lure. The image at right depicts this race. This attempt to provide a humane alternative to coursing failed, however, and the experiment would not be tried again until 1921.

From these coursing meets track racing would eventually develop. It came about partly due to the necessity of controlling the enormous crowds of people who came to observe the coursing. In an effort to keep them from trampling land, dogs, and other people, enclosed coursing parks were developed. These were huge fields which were fenced with an assortment of escapes (holes) built into the fences. Hares were captured and trained to the escapes so that they would have a fair chance. Then, during a coursing meet, dogs would be slipped in pairs to pursue the hare.

They were judged on speed on the "run up" to the hare, on the number and kind of turns they forced the hare to make (a sharp turn earned more points than a slight deviation), and on whether or not they made the kill. The "run up" earned a significant number of points so speed became very important. After an artificial lure was developed which could be run by a motor, it was an obvious step to turn to racing rather than coursing the hounds. The first artificial lure was used in England in 1876 [Mechanical Lure] and was a stuffed rabbit set up on a long rail that ran straight for a long distance, then went into a brushy blind.

This did not, however, prove popular and was dropped in favor of enclosed coursing. It was not until the early 1900s, when an American, Owen Patrick Smith, developed a lure that could be run in a circle on a track such as horses used that racing began to be considered as a sport.

With the formation of the National Coursing Club of England in 1858, coursing was turned into more of a business. It began requiring the registration of dogs for its events in 1882. This led to the creation of The Greyhound Stud Book in Britain and, later, sister publications in the US, Ireland and Australia.

The evolution from coursing to track racing began in 1876, when the first enclosed or "park" course meet was held. These courses were only 800 yards long instead of the 3-mile traditional courses. Because of this, enclosed courses put a premium on speed. Enclosed courses have stayed very popular in Ireland.

Their popularity in England was short-lived, but they helped convince open coursing leaders to shrink the size of their courses. Also in 1876, Greyhound racing began at the Welsh Harp, Hendon, England, when six dogs raced down a straight track after a mechanical lure. The image at right depicts this race. This attempt to provide a humane alternative to coursing failed, however, and the experiment would not be tried again until 1921.

From these coursing meets track racing would eventually develop. It came about partly due to the necessity of controlling the enormous crowds of people who came to observe the coursing. In an effort to keep them from trampling land, dogs, and other people, enclosed coursing parks were developed. These were huge fields which were fenced with an assortment of escapes (holes) built into the fences. Hares were captured and trained to the escapes so that they would have a fair chance. Then, during a coursing meet, dogs would be slipped in pairs to pursue the hare.

They were judged on speed on the "run up" to the hare, on the number and kind of turns they forced the hare to make (a sharp turn earned more points than a slight deviation), and on whether or not they made the kill. The "run up" earned a significant number of points so speed became very important. After an artificial lure was developed which could be run by a motor, it was an obvious step to turn to racing rather than coursing the hounds. The first artificial lure was used in England in 1876 [Mechanical Lure] and was a stuffed rabbit set up on a long rail that ran straight for a long distance, then went into a brushy blind.

This did not, however, prove popular and was dropped in favor of enclosed coursing. It was not until the early 1900s, when an American, Owen Patrick Smith, developed a lure that could be run in a circle on a track such as horses used that racing began to be considered as a sport.

Greyhounds in the New World

Spaniards brought Greyhounds with them to the new world. One Greyhound accompanied the conquistador Coronado all the way to present-day New Mexico.

A few Greyhounds existed in North America from colonial times. A Greyhound kept the German-born colonial military leader, Baron von Steuben, company through a long winter at Valley Forge. Greyhounds were imported to North America in large numbers from Ireland and England in the mid-1800s not to course or race, but to rid midwest farms of a virtual epidemic of jackrabbits that was ruining their farms.

Greyhounds also were used to hunt down coyotes who were killing livestock. They became familiar sights on farms and ranches in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas. Americans soon discovered that Greyhounds could be a source of sport. One of the first national coursing meets was held in Kansas in 1886. American coursing has been most popular in the western states.

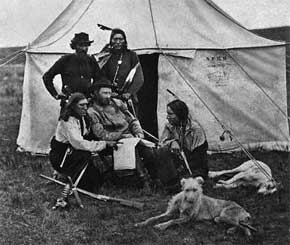

The US cavalry used Greyhounds as scouts to help spot Native Americans, since the Greyhounds were fast enough to keep up with the horses. General George Custer reportedly always took his 22 coursing Greyhounds with him when he travelled. Custer loved to nap on the parlor floor, surrounded by a sea of Greyhounds. He normally coursed his hounds the day before a battle, including the day before the Battle of Little Big Horn. (Left: photo of George A. Custer with the Sioux-Ree warrior Bloody Knife (pointing) and the Crow warrior Curly (standing), with staghound and greyhound in Montana, 1876.)

Spaniards brought Greyhounds with them to the new world. One Greyhound accompanied the conquistador Coronado all the way to present-day New Mexico.

A few Greyhounds existed in North America from colonial times. A Greyhound kept the German-born colonial military leader, Baron von Steuben, company through a long winter at Valley Forge. Greyhounds were imported to North America in large numbers from Ireland and England in the mid-1800s not to course or race, but to rid midwest farms of a virtual epidemic of jackrabbits that was ruining their farms.

Greyhounds also were used to hunt down coyotes who were killing livestock. They became familiar sights on farms and ranches in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas. Americans soon discovered that Greyhounds could be a source of sport. One of the first national coursing meets was held in Kansas in 1886. American coursing has been most popular in the western states.

The US cavalry used Greyhounds as scouts to help spot Native Americans, since the Greyhounds were fast enough to keep up with the horses. General George Custer reportedly always took his 22 coursing Greyhounds with him when he travelled. Custer loved to nap on the parlor floor, surrounded by a sea of Greyhounds. He normally coursed his hounds the day before a battle, including the day before the Battle of Little Big Horn. (Left: photo of George A. Custer with the Sioux-Ree warrior Bloody Knife (pointing) and the Crow warrior Curly (standing), with staghound and greyhound in Montana, 1876.)

The Waterloo Cup in Great Britain

Some of these meets, such as the Waterloo Cup, are still held today. The image above depicts coursing in the nineteenth century. At huge coursing grounds like Ashdown and Amesbury, spectators followed the dogs on horseback. In live-hare coursing, two Greyhounds are slipped (released) together. The winner is judged by a code of points: 1-3 for speed, 2-3 for the go-bye, 1 point for the turn (bringing the hare around at not less than a right angle), 1/2 point for the wrench (bringing the hare around at less than a right angle), 1-2 points for the kill, and 1 point for the trip (where the hare is thrown off its legs).

The Waterloo Cup was considered for over a century to be the ultimate test of the coursing Greyhound. The first Waterloo Cup was held in 1837 on the Altcar estate of Earl Sefton and was won by Mr. Stanton's dog, Fly. The competition was held during the week of the Grand National horse racing meet and soon attracted sporting men in considerable numbers. By the second half of the century, it had become a premier attraction by itself.

Modern Greyhound enthusiasts, whether of track or coursing sport, have little idea of how important this meet was. In fact, simply to be nominated for entry was a matter of prestige, and early advertisements for stud service or puppies would have a line reading "Waterloo Cup nominator" referring to the sire/stud. To actually win the Cup was to be the top dog of the year. To win it more than once was nearly unheard of. The great Greyhound, Master M'Grath won in 1868, 1869, and 1871! It was thought that the black dog's feat would never be bettered, but in 1889, Fullerton, a brindle, won his first Waterloo Cup. He would win it again in 1890, 1891, and unbelievably, for a fourth time in 1892.

Dogs were raised and trained in remote hill area where they could roam freely, and chase anything that caught their attention. The constant exercise and hard climate built a level of endurance into the dogs that some think has been lost with modern rearing methods. In their second spring, the puppies were either sold or began their training for coursing competition. Around the turn of the twentieth century the breeder Henry Thompson suspended on ropes near the kitchen range wooden boxes packed with straw, into which the puppies could climb to escape the cold draft on the floor.

Some of these meets, such as the Waterloo Cup, are still held today. The image above depicts coursing in the nineteenth century. At huge coursing grounds like Ashdown and Amesbury, spectators followed the dogs on horseback. In live-hare coursing, two Greyhounds are slipped (released) together. The winner is judged by a code of points: 1-3 for speed, 2-3 for the go-bye, 1 point for the turn (bringing the hare around at not less than a right angle), 1/2 point for the wrench (bringing the hare around at less than a right angle), 1-2 points for the kill, and 1 point for the trip (where the hare is thrown off its legs).

The Waterloo Cup was considered for over a century to be the ultimate test of the coursing Greyhound. The first Waterloo Cup was held in 1837 on the Altcar estate of Earl Sefton and was won by Mr. Stanton's dog, Fly. The competition was held during the week of the Grand National horse racing meet and soon attracted sporting men in considerable numbers. By the second half of the century, it had become a premier attraction by itself.

Modern Greyhound enthusiasts, whether of track or coursing sport, have little idea of how important this meet was. In fact, simply to be nominated for entry was a matter of prestige, and early advertisements for stud service or puppies would have a line reading "Waterloo Cup nominator" referring to the sire/stud. To actually win the Cup was to be the top dog of the year. To win it more than once was nearly unheard of. The great Greyhound, Master M'Grath won in 1868, 1869, and 1871! It was thought that the black dog's feat would never be bettered, but in 1889, Fullerton, a brindle, won his first Waterloo Cup. He would win it again in 1890, 1891, and unbelievably, for a fourth time in 1892.

Dogs were raised and trained in remote hill area where they could roam freely, and chase anything that caught their attention. The constant exercise and hard climate built a level of endurance into the dogs that some think has been lost with modern rearing methods. In their second spring, the puppies were either sold or began their training for coursing competition. Around the turn of the twentieth century the breeder Henry Thompson suspended on ropes near the kitchen range wooden boxes packed with straw, into which the puppies could climb to escape the cold draft on the floor.

Nineteenth Century

Greyhounds remained a familiar sight among the royalty and nobility of England in the nineteenth century. The husband of Queen Victoria had a pet black and white Greyhound, Eos. Eos appears in many court portraits.

This century saw the beginning of the advertising of dogs available to stud for a fee. This was a dramatic change from the past, when breeders would never allow one of their champions to sire a dog that might compete against them one day. King Cob was the first successful public stud dog. (Above: Dean Wolstenholme, Greyhounds Coursing a Hare, early 19th century England.)

The popularity of Greyhound coursing in Britain increased greatly in the nineteenth century, as the Industrial Revolution gave the manufacturing classes the wealth and time to enjoy such activities, and the expansion of rail made it easier to get to coursing events. Formal coursing meets reached their peak of popularity in the late 1800s.

Greyhounds remained a familiar sight among the royalty and nobility of England in the nineteenth century. The husband of Queen Victoria had a pet black and white Greyhound, Eos. Eos appears in many court portraits.

This century saw the beginning of the advertising of dogs available to stud for a fee. This was a dramatic change from the past, when breeders would never allow one of their champions to sire a dog that might compete against them one day. King Cob was the first successful public stud dog. (Above: Dean Wolstenholme, Greyhounds Coursing a Hare, early 19th century England.)

The popularity of Greyhound coursing in Britain increased greatly in the nineteenth century, as the Industrial Revolution gave the manufacturing classes the wealth and time to enjoy such activities, and the expansion of rail made it easier to get to coursing events. Formal coursing meets reached their peak of popularity in the late 1800s.

Eighteenth Century

The English Earl of Orford created the first coursing club open to the public in 1776 at Swaffham in Norfolk. At this same time, horse racing went public as well, and both sports became very popular with the public. Orford crossbred Greyhounds with several other breeds, including the bulldog, in pursuit of Greyhounds with greater stamina.

Despite legends to the contrary, his efforts were unsuccessful and there is no evidence that the bloodlines of these crosses survived. Later attempts to cross Greyhounds with Afghans also proved ineffective. One of the most famous Greyhounds of this century is Snowball, who won four cups and over thirty matches in his coursing career. In the eighteenth century breeders began to keep proper pedigrees of their dogs.

The English Earl of Orford created the first coursing club open to the public in 1776 at Swaffham in Norfolk. At this same time, horse racing went public as well, and both sports became very popular with the public. Orford crossbred Greyhounds with several other breeds, including the bulldog, in pursuit of Greyhounds with greater stamina.

Despite legends to the contrary, his efforts were unsuccessful and there is no evidence that the bloodlines of these crosses survived. Later attempts to cross Greyhounds with Afghans also proved ineffective. One of the most famous Greyhounds of this century is Snowball, who won four cups and over thirty matches in his coursing career. In the eighteenth century breeders began to keep proper pedigrees of their dogs.

By the close of the sixteenth century, the world had changed significantly. Feudalism had ended allowing commoners freedom of movement unknown for a thousand years. City dwellers increased in number. By this time many more people were able to own game dogs such as Greyhounds.

As the number of middle class persons expanded, so did the need for cleared land. Dense forests and swamps were giving way to planting land, pastures, and towns. These new fields brought infiltration by hares, foxes, and badgers. The need to exterminate unwanted animals led to breeding of cast-off Greyhounds (and other breeds) of the upper classes. (Above: François Desportes, Portrait of the Artist in Hunting Dress, 1699).

As the number of middle class persons expanded, so did the need for cleared land. Dense forests and swamps were giving way to planting land, pastures, and towns. These new fields brought infiltration by hares, foxes, and badgers. The need to exterminate unwanted animals led to breeding of cast-off Greyhounds (and other breeds) of the upper classes. (Above: François Desportes, Portrait of the Artist in Hunting Dress, 1699).

Unlike Elizabeth, King James I (1566-1625) preferred hunting to hard work. He was an avid fan of Greyhound coursing. Having heard about the strength of the local hares, he brought his Greyhounds to the village of Fordham near the border of Suffolk and Cambridge. This was not a public exhibition, but a private competition between the king's Greyhounds observed by James and his court. He stayed at the Griffin Innin the nearby town of Newmarket. He enjoyed the coursing there so much that he built a hunting lodge in Newmarket. To maintain the quality of hunting, in 1619 he ordered the release of 100 hares and 100 partridges every year at Newmarket. Races between the horses of his followers became as important as the matches between the king's Greyhounds. This began the tradition of competitive racing in Newmarket. (Right: Anthony Van Dyck, James Stuart, Duke of Richmond and Lennox, 1634.)

Dr. Caius' notes to the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner, written in 1570, describe the appearance and abilities of the English Greyhound (read an excerpt). In the late sixteenth century, Gervase Markham wrote that Greyhounds are of all dogs whatsoever the most noble and princely, strong, nimble, swift and valiant; and though of slender and very fine proportions, yet so well knit and coupled together, and so seconded with spirit and mettle, that they are master of all other dogs whatsoever.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) mentioned Greyhounds in a number of his plays (read Shakespeare excerpts at the Adopt A Greyhound website). In Henry V Henry's speech to his troops just before the Battle of Harfleur compares people to coursing Greyhounds:

I see you stand like Greyhounds in the slips,

Straining upon the start.

The game's afoot.

Dr. Caius' notes to the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner, written in 1570, describe the appearance and abilities of the English Greyhound (read an excerpt). In the late sixteenth century, Gervase Markham wrote that Greyhounds are of all dogs whatsoever the most noble and princely, strong, nimble, swift and valiant; and though of slender and very fine proportions, yet so well knit and coupled together, and so seconded with spirit and mettle, that they are master of all other dogs whatsoever.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) mentioned Greyhounds in a number of his plays (read Shakespeare excerpts at the Adopt A Greyhound website). In Henry V Henry's speech to his troops just before the Battle of Harfleur compares people to coursing Greyhounds:

I see you stand like Greyhounds in the slips,

Straining upon the start.

The game's afoot.

Often the hare escaped. Wagers were commonly placed on the racing dogs. Read theRenaissance rules of coursing, taken from a sixteenth century book by Gervase Markham, with my interpretations of their meanings. These rules were still in effect when the first official coursing club was founded in 1776 at Swaffham, Norfolk, England. The rules of coursing have not changed a great deal since this time. (Above: Jan Fyt, Diana with her Hunting Dogs Beside Kill, 17th century.)

Renaissance

Renaissance artists considered the Greyhound a worthy subject. The works of Veronese, Uccello, Pisanello and Desportes, among others, depict Greyhounds in a variety of setting from sacred to secular, with an emphasis on the hunt. (Above: Paolo Uccello, Night Hunt, 1460, in Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England.)

Coursing races, with dogs chasing live rabbits, became popular during the sixteenth century. Queen Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603) had Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, draw up rules judging competitive coursing. These rules established such things as the hare's head start and the ways in which the two hounds' speed, agility and concentration would be judged against one another. Winning was not necessarily dependent on catching the hare (although this did earn a high score).

Renaissance artists considered the Greyhound a worthy subject. The works of Veronese, Uccello, Pisanello and Desportes, among others, depict Greyhounds in a variety of setting from sacred to secular, with an emphasis on the hunt. (Above: Paolo Uccello, Night Hunt, 1460, in Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England.)

Coursing races, with dogs chasing live rabbits, became popular during the sixteenth century. Queen Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603) had Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, draw up rules judging competitive coursing. These rules established such things as the hare's head start and the ways in which the two hounds' speed, agility and concentration would be judged against one another. Winning was not necessarily dependent on catching the hare (although this did earn a high score).

We don't know for certain where or when the term Greyhound originated. It probably dates to the late middle ages. It may come from the old English "grei-hundr," supposedly "dog hunter" or high order of rank. Another explanation is that it is derived from "gre" or "gradus," meaning "first rank," so that Greyhound would mean "first rank among dogs." Finally, it has been suggested that the term derives from Greekhound, since the hound reached England through the Greeks. A minority view is that the original Greyhound stock was mostly grey in color, so that the name simply refers to the color of the hound. (Above: detail from Gaston Phoebus, "Veterinarians Treating Dogs," Book of the Hunt, c. 1500.)

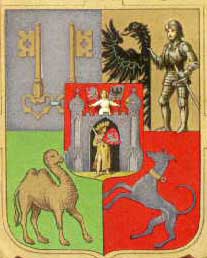

The Greyhound was used as an emblem, often in tombs, at the feet of the effigies of gentlemen, symbolizing the knightly virtues (faith), occupations (hunting) and generally the aristocratic way of life. Where tombs are concerned, the Greyhound always was associated with knighthood (along with the lion, symbolizing strength) and never with ladies, who generally were associated with the little lap-dog (symbol of marital faithfulness and domestic virtue). (Left: detail from the Plzen family coat of arms, c. 1578, depicting a greyhound.)

The Greyhound is the first breed of dog mentioned in English literature. The monk in Geoffrey Chaucer's 14th century The Canterbury Tales reportedly spent great sums on his Greyhounds.

Greyhounds he hadde as swifte as fowel in flight;

Of prikyng and of huntyng for the hare

Was al his lust, for no cost wolde he spare.

Edmund de Langley's Mayster of Game, AD 1370, describes the ideal Greyhound ( read an excerpt). Langley presented this book to the future King Henry V of England. Henry reportedly was a big fan of Greyhounds; perhaps Shakespeare knew this when, two centuries later, he had Henry speak the quote below.

The Greyhound is the first breed of dog mentioned in English literature. The monk in Geoffrey Chaucer's 14th century The Canterbury Tales reportedly spent great sums on his Greyhounds.

Greyhounds he hadde as swifte as fowel in flight;

Of prikyng and of huntyng for the hare

Was al his lust, for no cost wolde he spare.

Edmund de Langley's Mayster of Game, AD 1370, describes the ideal Greyhound ( read an excerpt). Langley presented this book to the future King Henry V of England. Henry reportedly was a big fan of Greyhounds; perhaps Shakespeare knew this when, two centuries later, he had Henry speak the quote below.

Hunting in Europe and Asia with specially bred and trained dogs was the sport of nobles and the clergy, in large part because they owned or controlled much of the land suitable for hunting. There's little evidence that the common man in the Middle Ages used dogs to hunt. Hunting with sighthounds in this era hadn't changed much since the time of Romans like Arrian. It was a sport, not the serious pursuit of food, which pitted the hounds against the hare and against each other. (Above: Gaston Phoebus, Book of the Hunt tapestry, c. 1500, Pierpont Morgan Library.)

Dogs in general were at times looked down upon in the Middle Ages, while Greyhounds were highly valued. Vincent of Beauvais, in the mid- thirteenth century, identified three types of dog: hunting dogs, with drooping ears, guard dogs, which are more rustic than other dogs, and Greyhounds, which are "the noblest, the most elegant, the swiftest, and the best at hunting."

Dogs in general were at times looked down upon in the Middle Ages, while Greyhounds were highly valued. Vincent of Beauvais, in the mid- thirteenth century, identified three types of dog: hunting dogs, with drooping ears, guard dogs, which are more rustic than other dogs, and Greyhounds, which are "the noblest, the most elegant, the swiftest, and the best at hunting."

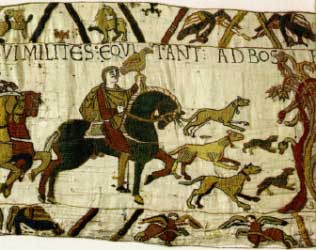

Middle Ages

Greyhounds nearly became extinct during times of famine in the Middle Ages. They were saved by clergymen who protected them and bred them for the nobility. From this point on, they came to be considered the dogs of the aristocracy. (Left: Gwydion ap Myrddin, Bayeux Tapestry, c.1084.) In the tenth century, King Howel of Wales made killing a Greyhound punishable by death. King Canute of England established the Forest Laws in 1014, reserving large areas of the country for hunting by the nobility. Only such persons could own Greyhounds; any "meane person" (commoner) caught owning a Greyhound would be severely punished and the dog's toes "lawed" (mutilated) to prevent it from hunting. In 1066 William the Conqueror introduced even more stringent forest laws. Commoners who hunted with Greyhounds in defiance of these laws favored dogs whose coloring made them harder to spot: black, red, fawn, and brindle. Nobles by contrast favored white and spotted dogs who could be spotted and recovered more easily if lost in the forest. It became common among the English aristocracy to say, "You could tell a gentleman by his horses and his Greyhounds." Old paintings and tapestries of hunting feasts often include Greyhounds.

Greyhounds nearly became extinct during times of famine in the Middle Ages. They were saved by clergymen who protected them and bred them for the nobility. From this point on, they came to be considered the dogs of the aristocracy. (Left: Gwydion ap Myrddin, Bayeux Tapestry, c.1084.) In the tenth century, King Howel of Wales made killing a Greyhound punishable by death. King Canute of England established the Forest Laws in 1014, reserving large areas of the country for hunting by the nobility. Only such persons could own Greyhounds; any "meane person" (commoner) caught owning a Greyhound would be severely punished and the dog's toes "lawed" (mutilated) to prevent it from hunting. In 1066 William the Conqueror introduced even more stringent forest laws. Commoners who hunted with Greyhounds in defiance of these laws favored dogs whose coloring made them harder to spot: black, red, fawn, and brindle. Nobles by contrast favored white and spotted dogs who could be spotted and recovered more easily if lost in the forest. It became common among the English aristocracy to say, "You could tell a gentleman by his horses and his Greyhounds." Old paintings and tapestries of hunting feasts often include Greyhounds.

Arab Tradition

The Arab peoples have kept Greyhound-type dogs for several thousand years. The Saluki (pictured at right), which almost certainly shares with the Greyhound a common ancestor, is still used as a hunting dog by some Arabs today. Arabian Bedouin for centuries have been devout Muslims, and so follow ritual restrictions against contact with dogs. But they don't consider their Salukis to be dogs and so don't believe that contact with them is unclean. The Quran permits the eating of game killed by hawks or Salukis (but not by other dogs). The Pashtun tribes in Afghanistan make the same distinction between Saluki and dog, so this probably goes back long before the birth of Islam in the seventh century. Bedouin so admired the physical attributes and speed of the Saluki that it was the only dog permitted to share their tents and ride atop their camels. In early Arabic culture, the birth of a Saluki ranked in importance just behind the birth of a son. The Bedouin use Salukis to hunt gazelle, hare, bustard (a type of bird), jackal, fox, and wild ass. They consider Salukis the Gift of Allah to his children.

The Arab peoples have kept Greyhound-type dogs for several thousand years. The Saluki (pictured at right), which almost certainly shares with the Greyhound a common ancestor, is still used as a hunting dog by some Arabs today. Arabian Bedouin for centuries have been devout Muslims, and so follow ritual restrictions against contact with dogs. But they don't consider their Salukis to be dogs and so don't believe that contact with them is unclean. The Quran permits the eating of game killed by hawks or Salukis (but not by other dogs). The Pashtun tribes in Afghanistan make the same distinction between Saluki and dog, so this probably goes back long before the birth of Islam in the seventh century. Bedouin so admired the physical attributes and speed of the Saluki that it was the only dog permitted to share their tents and ride atop their camels. In early Arabic culture, the birth of a Saluki ranked in importance just behind the birth of a son. The Bedouin use Salukis to hunt gazelle, hare, bustard (a type of bird), jackal, fox, and wild ass. They consider Salukis the Gift of Allah to his children.

The Romans used hounds for coursing. In coursing, the speed and agility of sighthounds are tested against their prey, the hare. Dogs apparently did not compete against one another, as in modern coursing. Ovid describes coursing in the early first century AD: the impatient Greyhound is held back to give the hare a fair start. The Roman Flavius Arrianus (Arrian) wrote "On Hunting Hares" in 124 AD. He tells his readers that the purpose of coursing is not to catch the hare, but to enjoy the chase itself: "The true sportsman does not take out his dogs to destroy the hares, but for the sake of the course and the contest between the dogs and the hares, and is glad if the hares escape." Concerned about proper sportsmanship, he adds, "Whoever courses with Greyhounds should neither slip them near the hare, nor more than a brace (2) at a time." Arrian also describes coursing among the Celts of Gaul (France):

The more opulent Celts, who live in luxury, course in the following manner. They send out hare finders early in the morning to look over such places as are likely to afford hares in form; and a messenger brings word if they have found any, and what number. They then go out themselves, and having started the hare, slip the dogs after her, and follow on horseback.

When they conquered Britain, the Romans brought with them European hares--more suitable for coursing than the local wild hares.

The more opulent Celts, who live in luxury, course in the following manner. They send out hare finders early in the morning to look over such places as are likely to afford hares in form; and a messenger brings word if they have found any, and what number. They then go out themselves, and having started the hare, slip the dogs after her, and follow on horseback.

When they conquered Britain, the Romans brought with them European hares--more suitable for coursing than the local wild hares.

Around 325 BC, a hound named Peritas reportedly accompanied the Macedonian monarch Alexander the Great on his military campaigns.

The Greek gods were often portrayed with Greyhounds. A hound often accompanies Hecate, the goddess of wealth. The protector of the hunt, the god Pollux, also is depicted with hounds. One myth tells of how a human named Actaeon came upon the goddess Artemis taking a bath in a river. She punishes his impropriety by turning him into a stag. He is then hunted down by his own hounds (depicted on a vase, above). Depictions of this scene occur many times in Greek and Roman art. In his work, Metamorphosis, the Roman writer Ovid in the late first century BC retold this story.

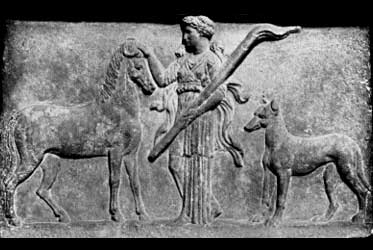

The Romans obtained their Greyhounds from either the Greeks or the Celts. Roman authors like Ovid and Arrian refer to them as Celt Hounds. Some of their deities were accompanied by hounds. Diana (the Roman version of Artemis) hunted with hounds. She was considered a patron deity of animals, as depicted in this relief sculpture. In a popular Roman story, Diana gives a Greyhound named Lelaps to her good friend Procris. Procris takes him hunting, and before long Procris spots a hare and pursues it. Unfortunately for Lelaps, the gods didn't want the hare to be caught and turned both Lelaps and the hare into stone. This scene is a common one in Roman art. Ovid also wrote about Procris and Lelaps (read an excerpt). (Above and below: Roman mosaics of Greyhound-type dogs, House of Dionysus, Paphos, Crete, second century AD.

The Greek gods were often portrayed with Greyhounds. A hound often accompanies Hecate, the goddess of wealth. The protector of the hunt, the god Pollux, also is depicted with hounds. One myth tells of how a human named Actaeon came upon the goddess Artemis taking a bath in a river. She punishes his impropriety by turning him into a stag. He is then hunted down by his own hounds (depicted on a vase, above). Depictions of this scene occur many times in Greek and Roman art. In his work, Metamorphosis, the Roman writer Ovid in the late first century BC retold this story.

The Romans obtained their Greyhounds from either the Greeks or the Celts. Roman authors like Ovid and Arrian refer to them as Celt Hounds. Some of their deities were accompanied by hounds. Diana (the Roman version of Artemis) hunted with hounds. She was considered a patron deity of animals, as depicted in this relief sculpture. In a popular Roman story, Diana gives a Greyhound named Lelaps to her good friend Procris. Procris takes him hunting, and before long Procris spots a hare and pursues it. Unfortunately for Lelaps, the gods didn't want the hare to be caught and turned both Lelaps and the hare into stone. This scene is a common one in Roman art. Ovid also wrote about Procris and Lelaps (read an excerpt). (Above and below: Roman mosaics of Greyhound-type dogs, House of Dionysus, Paphos, Crete, second century AD.

Ancient Greece and Rome

The Greeks probably bought some of these hounds from Egyptian merchants some time before 1000 BC. The first breed of dog named in western literature was the ancestor of the Greyhound. InThe Odyssey, written by Homer in 800 BC, the hero Odysseus is away from home for 20 years fighting the Trojans and trying to get home against the opposition of the god Poseidon. When he finally returns home, he disguises himself. The only one to recognize him was his hound Argus, who is described in terms that marks him clearly as a sighthound (read an excerpt). Art and coins from Greece depict short-haired hounds virtually identical to modern Greyhounds, making it fairly certain that the Greyhound breed has changed very little since 500 BC. A reason for the lack of change in 2,500 years is that, until very recently, the function of the Greyhound has remained the same: to thrill humans with its agility, speed, and intelligence as it chased the wild hare. (Above: Artemis as patron of the animals, around 350 BC.)

The Greeks probably bought some of these hounds from Egyptian merchants some time before 1000 BC. The first breed of dog named in western literature was the ancestor of the Greyhound. InThe Odyssey, written by Homer in 800 BC, the hero Odysseus is away from home for 20 years fighting the Trojans and trying to get home against the opposition of the god Poseidon. When he finally returns home, he disguises himself. The only one to recognize him was his hound Argus, who is described in terms that marks him clearly as a sighthound (read an excerpt). Art and coins from Greece depict short-haired hounds virtually identical to modern Greyhounds, making it fairly certain that the Greyhound breed has changed very little since 500 BC. A reason for the lack of change in 2,500 years is that, until very recently, the function of the Greyhound has remained the same: to thrill humans with its agility, speed, and intelligence as it chased the wild hare. (Above: Artemis as patron of the animals, around 350 BC.)

Greyhounds in Antiquity

Ancient Egypt

In Egypt, the ancestors of modern Greyhounds were used in hunting and kept as companions. Many Egyptians considered the birth of a such a hound second in importance only to the birth of a son. When the pet hound died, the entire family would go into mourning. The favorite hounds of the upper class were mummified and buried with their owners. The walls of Egyptian tombs often were decorated with images of their hounds. An Egyptian tomb painting from 2200 BC portrays dogs that looks very much like the modern Greyhound (for a picture of this mural, see The Complete Book of Greyhounds,, p. 8).

Among pharaohs known to own Greyhound-type dogs are Tutankhamen, Amenhotep II, Thutmose III, Queen Hatshepsut, and Cleopatra VII (of Antony and Cleopatra fame).

The Egyptian god Anubis, either a jackal or a hound-type dog, is frequently displayed on murals in the tombs of the Pharaohs (statue at left). Some depictions of it look much like the modern Pharaoh Hound, a close relation of the Greyhound.

The Bible

The only breed of dog mentioned by name in the Bible is the Greyhound (Proverbs 30:29-31, King James Version):

There be three things which do well, yea,

Which are comely in going;

A lion, which is strongest among beasts and

Turneth not away from any;

A Greyhound;

A he-goat also.

The Hebrew phrase translated as "Greyhound" literally means "girt in the loins." This probably was considered by translators the most appropriate English term to describe the ancestor of the Greyhound. It also didn't hurt that Greyhound coursing was popular with the sixteenth century court of King James (see below).

In the Jewish and Christian scriptures, dogs are generally considered ill- tempered scavengers which are tolerated but not trusted; certainly not admired and loved. In several passages, it's clear that dogs were thought of as scavengers: "Any one belonging to Jeroboam who dies in the city the dogs shall eat. . . " (1 Kings 14:11).

A pack of dogs might threaten one's safety: "Yea, dogs are round about me; a company of evildoers encircle me. . ." (Psalm 22:16). One might well have to beat them off for protection: "And the Philistine said to David, 'Am I a dog, that you come to me with sticks?'" (1 Samuel 17:43).

A strange dog might quickly become vicious if riled: "He who meddles in a quarrel not his own is like one who takes a passing dog by the ears" (Proverbs 26:17). Jesus refers to their role as scavengers when he says, "It is not fair to take the children's bread and throw it to the dogs" (Matthew 15:26).

Ancient Egypt

In Egypt, the ancestors of modern Greyhounds were used in hunting and kept as companions. Many Egyptians considered the birth of a such a hound second in importance only to the birth of a son. When the pet hound died, the entire family would go into mourning. The favorite hounds of the upper class were mummified and buried with their owners. The walls of Egyptian tombs often were decorated with images of their hounds. An Egyptian tomb painting from 2200 BC portrays dogs that looks very much like the modern Greyhound (for a picture of this mural, see The Complete Book of Greyhounds,, p. 8).

Among pharaohs known to own Greyhound-type dogs are Tutankhamen, Amenhotep II, Thutmose III, Queen Hatshepsut, and Cleopatra VII (of Antony and Cleopatra fame).

The Egyptian god Anubis, either a jackal or a hound-type dog, is frequently displayed on murals in the tombs of the Pharaohs (statue at left). Some depictions of it look much like the modern Pharaoh Hound, a close relation of the Greyhound.

The Bible

The only breed of dog mentioned by name in the Bible is the Greyhound (Proverbs 30:29-31, King James Version):

There be three things which do well, yea,

Which are comely in going;

A lion, which is strongest among beasts and

Turneth not away from any;

A Greyhound;

A he-goat also.

The Hebrew phrase translated as "Greyhound" literally means "girt in the loins." This probably was considered by translators the most appropriate English term to describe the ancestor of the Greyhound. It also didn't hurt that Greyhound coursing was popular with the sixteenth century court of King James (see below).

In the Jewish and Christian scriptures, dogs are generally considered ill- tempered scavengers which are tolerated but not trusted; certainly not admired and loved. In several passages, it's clear that dogs were thought of as scavengers: "Any one belonging to Jeroboam who dies in the city the dogs shall eat. . . " (1 Kings 14:11).

A pack of dogs might threaten one's safety: "Yea, dogs are round about me; a company of evildoers encircle me. . ." (Psalm 22:16). One might well have to beat them off for protection: "And the Philistine said to David, 'Am I a dog, that you come to me with sticks?'" (1 Samuel 17:43).

A strange dog might quickly become vicious if riled: "He who meddles in a quarrel not his own is like one who takes a passing dog by the ears" (Proverbs 26:17). Jesus refers to their role as scavengers when he says, "It is not fair to take the children's bread and throw it to the dogs" (Matthew 15:26).

Where did the Greyhound-type dog originate? The testimony of the ancients is inconsistent on this point. The Romans believed that Greyhounds came from Gaul (western Europe), the land of the Celts. The Celts, on the other hand, believed that Greyhounds came from Greece, and so called them "Greek hounds" (Greyhound may in fact be a derivation of Greek hound). (Left: detail from Paolo Uccello, Night Hunt, 1460, in Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England. See the entire work below.)

It is most likely that the ancestor of Greyhounds and other sighthounds first came into being in the tents of Middle Eastern nomadic peoples. Some think that the sighthound is a cross between the domesticated dog of that era and the southern European wolf. In a movable camp setting, it was common for dogs to follow the camp, eating from its trash and protecting its unwalled perimeter. The presence of these dogs was tolerated because of the guard service they provided. But they were regarded as wild and disagreeable by people, a belief to which most references to dogs in the Bible testify.

But at some point, a special kind of dog was discovered or bred--a dog that could hunt along with humans, even humans on horseback-- an extremely valuable service. These dogs had to be kept separate from the dogs on the camp's perimeter, so that interbreeding wouldn't ruin the special abilities of these proto-Greyhounds. So these sighthounds were given a special place inside the camp, even inside the tents, where no other animal was allowed, so that their breeding might be controlled. The unique and highly prized abilities of sighthounds help explain why they have changed very little in 2,000 years.

It is most likely that the ancestor of Greyhounds and other sighthounds first came into being in the tents of Middle Eastern nomadic peoples. Some think that the sighthound is a cross between the domesticated dog of that era and the southern European wolf. In a movable camp setting, it was common for dogs to follow the camp, eating from its trash and protecting its unwalled perimeter. The presence of these dogs was tolerated because of the guard service they provided. But they were regarded as wild and disagreeable by people, a belief to which most references to dogs in the Bible testify.

But at some point, a special kind of dog was discovered or bred--a dog that could hunt along with humans, even humans on horseback-- an extremely valuable service. These dogs had to be kept separate from the dogs on the camp's perimeter, so that interbreeding wouldn't ruin the special abilities of these proto-Greyhounds. So these sighthounds were given a special place inside the camp, even inside the tents, where no other animal was allowed, so that their breeding might be controlled. The unique and highly prized abilities of sighthounds help explain why they have changed very little in 2,000 years.

Image credits:

"Anubis," "Actaeon," and "Artemis": Dan Schmidt's Adopt A Greyhound web site's Gallery of Greyhound art pages. Reproduced by permission.

Desportes: Francois Desportes, Portrait of the Artist in Hunting Dress (1699), Musee du Louvre, Paris Image courtesy of Mark Harden. Reproduced by permission.

"Lure Coursing" and "Mechanical Lure": Copyrighted by A Breed Apart online magazine, edited by Bruce Skinner. They appear in"Born to The Purple? A Heritage of Greyhounds" by Laurel E. Drew. Reproduced by permission.

Sources:

Julia Barnes, ed., The Complete Book of Greyhounds, New York: Howell Book House, 1994.

Cynthia Brannigan, Adopting the Racing Greyhound, New York: Howell Book House, 1992.

D. Caroline Coile, Greyhounds: A Complete Pet Owner's Manual, New York: Barron's, 1996.

Joan Belle Isle, "Who's On First Now? The Greyhound Racing Industry Explained," Celebrating Greyhounds Spring 2008.

"Anubis," "Actaeon," and "Artemis": Dan Schmidt's Adopt A Greyhound web site's Gallery of Greyhound art pages. Reproduced by permission.

Desportes: Francois Desportes, Portrait of the Artist in Hunting Dress (1699), Musee du Louvre, Paris Image courtesy of Mark Harden. Reproduced by permission.

"Lure Coursing" and "Mechanical Lure": Copyrighted by A Breed Apart online magazine, edited by Bruce Skinner. They appear in"Born to The Purple? A Heritage of Greyhounds" by Laurel E. Drew. Reproduced by permission.

Sources:

Julia Barnes, ed., The Complete Book of Greyhounds, New York: Howell Book House, 1994.

Cynthia Brannigan, Adopting the Racing Greyhound, New York: Howell Book House, 1992.

D. Caroline Coile, Greyhounds: A Complete Pet Owner's Manual, New York: Barron's, 1996.

Joan Belle Isle, "Who's On First Now? The Greyhound Racing Industry Explained," Celebrating Greyhounds Spring 2008.